Definition

An Anal Fissure is a linear tear in the delicate mucosal lining of the anal canal, typically located in the posterior midline, and represents one of the most frequent causes of severe anal pain during bowel movements. The fissure disrupts the normal integrity of the anoderm, exposing sensitive nerve endings that trigger sharp, burning, or cutting pain, often accompanied by bright red rectal bleeding.

Although a fissure may appear minor in size, its impact on daily comfort can be significant due to the rich nerve supply of the anal region. As the tear persists, the internal anal sphincter frequently responds with involuntary spasm, which further reduces blood flow to the injured tissue and impairs the natural healing process. This combination of mechanical tearing, neural sensitivity, and vascular compromise explains why even a small fissure can produce profound discomfort and lead to chronicity if not properly managed.

An anal fissure may occur in individuals of all ages, from infants to adults, but is especially common among those with constipation, hard stool formation, or irregular bowel habits. When defecation requires excessive straining, the mucosal lining is stretched beyond its natural capacity, resulting in tearing. The tissue’s inability to maintain elasticity and withstand pressure is influenced by hydration status, dietary fiber intake, and sphincter muscle function.

Some patients also experience psychological components such as anxiety or fear of defecation, which can cause further tightening of the internal sphincter and perpetuate the cycle of pain and delayed healing. For many individuals, symptoms appear suddenly after a single episode of difficult bowel movement, while for others, recurrent trauma leads to repeated fissure formation.

Anatomy Background

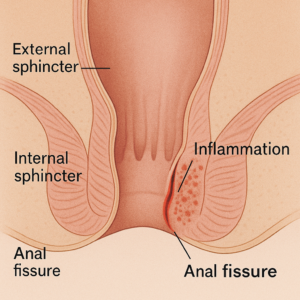

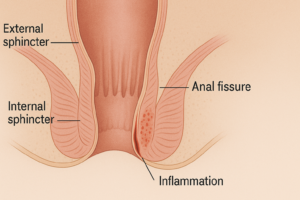

To understand how an anal fissure forms, it is essential to recognize the unique anatomy of the anal canal. The canal is lined with anoderm, a thin, highly sensitive layer that contains numerous nerve endings responsible for precise detection of stool consistency, gas, and liquid. Unlike other areas of the gastrointestinal tract, the anoderm lacks a thick protective mucous layer, making it vulnerable to mechanical injury.

Beneath this lining lies the internal anal sphincter, a circular smooth muscle that remains involuntarily contracted to maintain continence. When the sphincter becomes excessively tight, whether due to stress, pain, or physiological predisposition, blood flow to the posterior midline decreases significantly. This region naturally has the poorest perfusion, which is why fissures most commonly occur there.

In a healthy state, the anal lining regenerates rapidly; however, when perfusion is compromised, tissue repair slows, and even minor injury can develop into a chronic wound. Chronic fissures exhibit classic features such as a sentinel skin tag at the external margin and a hypertrophied papilla inside the canal. These changes reflect prolonged irritation and the body’s attempts to protect the area. Understanding this anatomy helps clinicians determine why conservative treatment succeeds for some patients while others require more advanced interventions. For personalized evaluation and care, patients may consult our Proctologist at Concierge Medical Center.

Causes

The causes of an Anal Fissure are closely linked to mechanical stress, impaired mucosal integrity, and abnormal sphincter physiology. The most common and well-established cause is chronic constipation, which forces individuals to strain excessively during bowel movements. Hard, dry stools exert pressure on the anoderm, stretching it beyond normal capacity and leading to abrupt tearing. Repetitive trauma from ongoing constipation not only causes new fissures but also prevents existing ones from healing fully, creating a cycle of pain, fear, and delayed recovery.

Many patients describe a pattern in which the initial injury triggers severe discomfort, causing them to avoid defecation, which in turn worsens constipation and increases the likelihood of re-injury.

Another significant cause is chronic diarrhea. Although less commonly associated with fissures compared to constipation, persistent loose stools irritate the anal mucosa, disrupt the natural pH balance, and cause inflammation of the anoderm. This chronic irritation weakens the protective epithelial layer, making it more susceptible to tearing even with minimal mechanical force.

Infections, food intolerances, and inflammatory bowel diseases frequently contribute to diarrhea-related fissures. When inflammation is ongoing, the mucosa becomes fragile, and normal bowel movements may cause micro-abrasions that evolve into deeper fissures.

Anal sphincter hypertonicity plays a major pathophysiological role in fissure development. Individuals with heightened resting sphincter pressure experience reduced blood supply to the posterior midline of the anal canal—an area already known for its relatively poor perfusion. When blood flow decreases, tissue elasticity and regenerative capacity diminish, making the anoderm highly vulnerable to injury.

Contributing factors include stress, anxiety, pelvic floor dysfunction, and autonomic nervous system imbalance. Even minor trauma can result in persistent tears due to impaired healing.

Obstetric trauma represents another well-recognized cause. During childbirth, significant stretching of the perineal tissues may injure the anal mucosa or disrupt the underlying sphincter muscles. Women who deliver large infants, undergo forceps or vacuum-assisted delivery, or experience perineal tearing are at higher risk. Hormonal changes and postpartum constipation further exacerbate the likelihood of fissure formation in the months following delivery.

Other direct mechanical injuries include anal intercourse, insertion of foreign bodies, forceful wiping, and traumatic medical procedures such as rectal examinations in patients with heightened sensitivity. These events can create micro-tears that rapidly enlarge when sphincter spasm restricts blood flow.

Systemic conditions also contribute to fissure formation. Diseases such as Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, HIV, syphilis, leukemia, and tuberculosis can weaken the mucosa or compromise immune response. Fissures associated with systemic disorders are often atypical in location—appearing laterally rather than midline—and tend to become chronic more quickly. When fissures fail to heal despite appropriate therapy, clinicians must evaluate for underlying pathology.

Proper identification of the cause ensures targeted, effective treatment and significantly reduces recurrence risk. For further evaluation, patients can schedule a consultation with our Proctologist at Concierge Medical Center.

Symptoms

The symptoms of an Anal Fissure are often unmistakable due to their intensity and highly localized nature. The most defining symptom is sharp, cutting pain during or immediately after a bowel movement. Many patients describe the sensation as “glass tearing the skin,” followed by lingering burning or throbbing discomfort that may persist from a few minutes to several hours. This prolonged pain is largely caused by involuntary spasm of the internal anal sphincter, which tightens in response to injury and further reduces blood flow to the affected area.

Over time, the fear of experiencing this pain may lead individuals to delay defecation, triggering constipation and worsening the underlying condition. This creates a vicious cycle in which pain leads to avoidance, avoidance leads to harder stool, and harder stool results in deeper fissuring.

Another common symptom is bright red bleeding, typically noticed on toilet paper or the surface of the stool. Unlike bleeding from deeper gastrointestinal sources, fissure-related bleeding tends to be minimal and clearly visible at the end of defecation. Additional symptoms include itching, irritation, and a sensation of tearing at the anal opening. Some patients experience increased moisture or discharge due to inflammation of the surrounding tissue.

In chronic cases, a small skin tag known as a sentinel pile may form at the outer edge of the fissure. This skin tag does not represent a separate disease but rather a protective reaction of the body to prolonged irritation.

Pain intensity may vary depending on the location and depth of the fissure. Posterior fissures tend to be more painful because the posterior midline receives less blood supply, slowing natural healing. Fissures that develop in unusual locations—such as the lateral or anterior regions—may cause atypical patterns of discomfort and are often associated with systemic illnesses like Crohn’s disease or infections. Understanding symptom patterns helps clinicians distinguish simple acute fissures from complex or chronic conditions requiring specialized intervention.

Red-Flag Symptoms

While most anal fissures are benign and heal with conservative treatment, certain symptoms should alert patients to seek medical care promptly. Heavy or persistent bleeding is the first warning sign, particularly when the amount exceeds a few drops or occurs independently of bowel movements. Bleeding that saturates toilet paper or drips into the toilet bowl may indicate a deeper tear or coexisting anorectal disorder.

Fever, swelling, purulent discharge, or increasing redness around the anal area suggest possible infection or the development of an abscess. Severe or worsening pain that prevents sitting, walking, or sleeping also deserves immediate evaluation. Fissures located outside the typical posterior midline position are red flags because they may reflect inflammatory bowel disease, trauma, sexually transmitted infections, or systemic pathology. Chronic fissures that fail to improve after six to eight weeks of appropriate therapy require further diagnostic workup to rule out underlying disease.

Patients experiencing any of these concerning signs should schedule prompt evaluation with a specialist. Our Proctologist at Concierge Medical Center provides thorough assessment, ensuring timely detection and effective management of both typical and atypical fissures.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of an Anal Fissure is primarily clinical and often straightforward, based on a detailed medical history and a careful physical examination. During assessment, the proctologist begins by asking about the onset, character, and duration of pain, as well as bowel movement patterns, dietary habits, and any previous episodes of similar symptoms. Many patients describe the classic pattern of severe sharp pain during defecation followed by prolonged burning or throbbing discomfort, which strongly suggests a fissure.

Visual inspection of the anal region is usually sufficient to identify the tear, which typically appears as a linear ulcer with fresh edges in acute cases or fibrotic, raised edges in chronic cases. The posterior midline location is most common, but fissures occurring in atypical positions require closer investigation.

A digital rectal examination is often avoided initially because the intense pain may cause significant distress and spasm; however, once symptoms improve or with adequate anesthesia, gentle palpation may help evaluate sphincter tone and rule out additional pathology.

Anoscopy and proctoscopy are valuable tools when visualization is needed to examine deeper structures, particularly in chronic fissures or when internal complications such as hypertrophied papilla or sentinel piles are suspected. In cases of recurrent, atypical, or non-healing fissures, further evaluation may include colonoscopy to rule out inflammatory bowel disease, colorectal cancer, or other mucosal abnormalities. Stool tests, blood work, and screening for infectious diseases may also be required when systemic illness is suspected.

Differential Diagnosis

Although anal fissures have characteristic features, several other anorectal conditions may mimic their symptoms. Hemorrhoids are one of the most common differential diagnoses because they also present with bright red bleeding and discomfort during defecation. However, hemorrhoidal pain tends to be less sharp and more related to swelling or thrombosis. A physical examination readily distinguishes these two conditions because fissures appear as visible tears, while hemorrhoids present as vascular cushions or swollen veins.

Anorectal abscess must be excluded when patients report severe constant pain, fever, localized swelling, or purulent discharge. Unlike fissure-related pain, abscess discomfort is persistent rather than triggered specifically by bowel movements. Early detection is essential because untreated abscesses may progress to fistula formation. Anal fistulas themselves may also mimic chronic fissures, particularly when drainage or irritation occurs. Fistulas typically involve abnormal tracts between the anal canal and perianal skin and require imaging or probing for confirmation.

Crohn’s disease is a critical component of the differential diagnosis, especially when fissures occur laterally or appear multiple. Crohn’s-related fissures tend to be deeper, irregular, and resistant to standard therapy. Additional symptoms such as chronic diarrhea, unexplained weight loss, abdominal pain, and perianal skin changes may provide diagnostic clues. Other potential causes include sexually transmitted infections such as syphilis, HIV, herpes simplex virus, and chlamydia, all of which can impair mucosal integrity or mimic ulcerative lesions. Malignancies such as anal carcinoma must also be considered when patients present with persistent non-healing fissures, particularly in older adults or individuals with risk factors.

A precise diagnosis ensures that patients receive appropriate treatment rather than prolonged ineffective care. Our Proctologist at Concierge Medical Center performs comprehensive evaluation to distinguish fissures from other anorectal disorders and guide effective, individualized management.

Treatment

Effective treatment of an Anal Fissure focuses on relieving pain, reducing internal sphincter spasm, improving blood flow, and promoting sustained wound healing. The initial approach almost always begins with conservative management because the majority of acute fissures heal without the need for surgical intervention. Warm sitz baths, performed two or three times daily, help relax the internal anal sphincter, soothe irritated tissue, and temporarily improve blood supply. Increased dietary fiber intake through fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and supplemental fiber powders softens stool consistency, making bowel movements less traumatic.

Many clinicians recommend a daily water intake above two liters to further prevent dehydration-related constipation. These foundational lifestyle adjustments are supported by guidelines from leading medical authorities such as the Mayo Clinic, which emphasizes noninvasive care as the first-line strategy.

Topical pharmacologic therapy plays a central role in improving healing. Nitroglycerin ointment is one of the most widely used agents; it works by relaxing the internal sphincter, thereby increasing perfusion to the fissure site. Although some patients experience headaches due to vasodilation, its documented clinical effectiveness keeps it among the recommended treatments by institutions including the Cleveland Clinic. Calcium channel blockers such as diltiazem and nifedipine, typically formulated as creams or gels, offer another effective option with fewer side effects.

Many specialists prefer these agents for long-term or sensitive patients who cannot tolerate nitroglycerin. Additionally, topical anesthetics like lidocaine may provide short-term reduction of acute pain, enabling more comfortable bowel movements and breaking the fear–constipation cycle.

Botulinum toxin (Botox) injection is a minimally invasive yet highly successful next step when conservative measures fail after several weeks. Botox temporarily paralyzes a portion of the internal sphincter, reducing resting pressure and allowing the fissure to heal naturally.

Its success rates approach 70–90% according to multiple clinical studies summarized by PubMed-reviewed research. The procedure is quick, safe, and often preferred by patients wishing to avoid surgery. However, because its effects are temporary, some individuals may require repeat injections or additional conservative measures to prevent recurrence.

For chronic fissures that persist beyond eight to twelve weeks or fail medication-based therapies, surgical management becomes the gold standard. Lateral internal sphincterotomy (LIS) is the most effective and widely accepted operative treatment. By partially dividing the internal sphincter muscle, the procedure reduces pathologic hypertonicity, restores normal blood flow, and achieves healing rates over 90%. Recovery is typically rapid, and most patients experience dramatic pain reduction within days.

Although rare, potential complications include minor incontinence, which is why careful patient selection and evaluation by an experienced specialist are essential. Postoperative recommendations include high-fiber diets, adequate hydration, stool softeners, and continued attention to anal hygiene to minimize the risk of recurrence.

ICD-10 Code

Anal fissures are classified within the international ICD-10 coding framework as follows:

K60.0 — Acute Anal Fissure: Characterized by a fresh mucosal tear without chronic features.

K60.2 — Chronic Anal Fissure: Marked by persistent tissue changes such as indurated edges, sentinel pile, and hypertrophied papillae.

Accurate coding ensures proper documentation, continuity of medical care, and appropriate treatment planning within clinical settings.

When to See a Doctor

Patients should seek medical care whenever anal pain persists beyond a few bowel movements, when bleeding occurs frequently, or when symptoms interfere with daily activities. Persistent fissures lasting more than six weeks often indicate chronicity and require targeted treatment strategies. Severe pain preventing sitting, walking, or sleeping is another clear reason for urgent evaluation.

Fever, foul-smelling discharge, or swelling around the anal area may signal an infection or an emerging abscess, both of which require immediate professional attention. Fissures located in atypical positions—such as lateral or anterior regions—should always prompt investigation for underlying systemic diseases including Crohn’s disease, HIV, or other inflammatory conditions.

Patients who notice recurrent fissures, unexplained weight loss, persistent diarrhea, or a lack of improvement despite appropriate therapy should undergo further diagnostic evaluation. Early intervention can prevent complications, minimize chronic pain, and shorten recovery time. Individuals seeking comprehensive assessment, evidence-based treatments, and personalized care plans may schedule a consultation with our Proctologist at Concierge Medical Center. Following recommended guidelines from sources such as the MedlinePlus medical library helps ensure patients receive high-quality, scientifically grounded care.