What is Migraine?

Understanding a Neurological Condition That Affects Millions

This condition, often mistaken for a simple headache, is actually a complex disorder of the nervous system. It presents as recurring episodes of intense head pain, which may last from a few hours to several days. These episodes are frequently accompanied by visual disturbances, heightened sensitivity to light or sound, and gastrointestinal symptoms like nausea. What makes this disorder particularly challenging is its unpredictability and its ability to interfere with normal life.

Historically, this neurological phenomenon has been documented as far back as ancient civilizations. References to one-sided head pain and associated vision changes appear in Greek medical texts and were also described in medieval Persian medicine. Despite centuries of awareness, its underlying mechanisms remain only partially understood even in modern neurology.

Impact on Daily Function and Well-Being

Unlike tension headaches, which are typically manageable and short-lived, this condition can render a person unable to concentrate, work, or even communicate. Some patients find it impossible to be exposed to light, movement, or sound without their symptoms worsening. Others retreat to dark, quiet rooms until the worst passes. In extreme cases, sufferers may experience transient neurological symptoms that mimic more serious events such as strokes.

Who Is Affected and When It Begins

Although people of all ages and backgrounds can experience these attacks, it most commonly begins during puberty or early adulthood. Epidemiological data show that it affects approximately 1 in 7 people globally. In women, the prevalence is notably higher—almost three times that of men—which many experts attribute to hormonal fluctuations during the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, or menopause.

Children and teenagers are not immune. In fact, young people who report unexplained stomach pain, dizziness, or aversion to light and noise may be showing early signs. Pediatric neurologists are increasingly recognizing the need for early diagnosis to prevent the condition from progressing into more chronic forms later in life.

Common Misunderstandings

A major barrier to treatment is public misconception. Many assume this condition is simply an exaggerated headache. Others may dismiss a person’s suffering because there are no visible symptoms. This has led to underdiagnosis and stigmatization, even in clinical settings. A better understanding of the condition as a multifactorial neurological syndrome—rather than just a pain episode—can shift both public and professional attitudes toward timely intervention and compassionate care.

While a cure remains elusive, effective management strategies are available. These range from pharmacologic treatments and behavioral therapy to lifestyle adjustments and specialized medical consultation.

Causes and Triggers of Migraine

Exploring the Underlying Mechanisms and Everyday Provocateurs

Understanding what initiates these debilitating neurological episodes is crucial for effective prevention. Although researchers haven’t pinpointed a singular cause, the consensus is that this condition is multifactorial—resulting from a combination of genetic, environmental, and neurovascular influences. Individuals with a family history of similar attacks are significantly more likely to develop the disorder, suggesting a strong hereditary component. But hereditary predisposition alone is not enough to provoke an episode; specific triggers are often the catalyst.

Hormonal Shifts

Hormonal changes are among the most common and well-documented factors. Many women report increased episodes during menstruation, ovulation, pregnancy, or menopause. This correlation is largely attributed to fluctuating levels of estrogen and progesterone, which can influence neurotransmitter activity in the brain. Hormone-based birth control methods and hormone replacement therapy may either help or worsen the frequency of attacks, depending on the individual’s sensitivity.

Dietary Factors

Numerous foods and beverages have been identified as common triggers. These include aged cheeses, processed meats, red wine, artificial sweeteners, and caffeine—both excessive consumption and sudden withdrawal. It’s important to understand that dietary triggers vary from person to person, and keeping a food diary may help identify which substances provoke symptoms in each case.

Sleep and Stress

Inconsistent sleep patterns, including both deprivation and oversleeping, can activate attacks. Likewise, emotional stress is a significant contributor. Interestingly, many people experience an attack not during a stressful period, but shortly afterward, during the “let-down” phase. The body’s neurochemical responses to stress—including changes in cortisol and serotonin—are believed to play a major role.

Sensory Stimuli

Flashing lights, loud noises, strong smells, and even subtle environmental changes such as weather pressure shifts can act as triggers. Bright screens, perfumes, cigarette smoke, or even changing altitudes (such as air travel or mountain climbing) may provoke an episode. Some individuals report experiencing heightened sensory sensitivity even before the pain begins, signaling an oncoming attack.

Physical Activity and Dehydration

Though moderate exercise is generally beneficial, sudden intense activity can occasionally initiate symptoms—especially if combined with inadequate hydration or skipped meals. Dehydration and low blood sugar levels are two of the most underestimated contributing factors and are especially relevant in warm climates or during periods of fasting.

Weather and Barometric Pressure

Changes in the weather—particularly shifts in barometric pressure—can trigger neurological instability in susceptible individuals. Many people find that stormy, humid, or excessively bright conditions correlate with their attacks. While the exact mechanism remains unclear, the link between atmospheric changes and symptom onset is well-documented anecdotally and supported by emerging research.

It’s important to recognize that what provokes an attack in one person may have no effect on another. Triggers are highly individualized and may also change over time. The best strategy is a proactive one: identify patterns, maintain consistency in daily habits, and avoid known provocateurs when possible. For many patients, a combination of medical treatment and lifestyle awareness significantly reduces the frequency and intensity of these episodes.

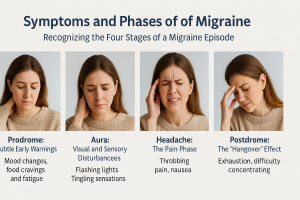

Symptoms and Phases of Migraine

Recognizing the Four Stages of a Migraine Episode

What makes this condition particularly challenging is its phased nature. It doesn’t always begin with pain, and it certainly doesn’t end with it. Neurological episodes often unfold across multiple stages, each with distinct symptoms. These stages can vary in duration, intensity, and visibility, which is why many people fail to recognize early warning signs before the full onset of discomfort.

1. Prodrome: Subtle Early Warnings

This first phase occurs hours—or even a full day—before noticeable head pain begins. Individuals may experience mood changes, neck stiffness, food cravings, frequent yawning, or sensitivity to light and sound. Some describe a general feeling of unease, difficulty concentrating, or unusual fatigue. Recognizing these early signs can allow timely interventions, potentially reducing the severity of the attack.

2. Aura: Visual and Sensory Disturbances

About 25–30% of sufferers report experiencing an “aura” before or during their main symptoms. This may include flashing lights, zigzag lines, blind spots, or even temporary visual loss. Others report tingling sensations in the hands or face, speech difficulty, or auditory distortions. While auras typically last 20 to 60 minutes, they can be alarming and are sometimes confused with signs of stroke or other neurological events.

3. Headache: The Pain Phase

This is the most recognizable stage and typically lasts from 4 to 72 hours. The pain is often described as throbbing or pulsating, usually affecting one side of the head, though both sides can be involved. Physical activity, movement, or even coughing may intensify the pain. During this phase, individuals may also experience nausea, vomiting, blurred vision, and extreme sensitivity to external stimuli such as sound, light, or smell.

4. Postdrome: The “Hangover” Effect

Once the intense pain subsides, many patients report a lingering period of exhaustion, brain fog, dizziness, and sensitivity. Known as the “migraine hangover,” this phase can last up to 24 hours. During this time, individuals may feel emotionally drained, mentally slow, or physically weak. Although the pain is gone, the body is still recovering from the neurological and vascular strain of the episode.

It’s important to note that not every individual experiences all four stages. Some may go straight to the pain phase, while others may experience aura without headache. This variability makes diagnosis and treatment highly personalized. Understanding the full cycle, however, can empower patients to act early and manage symptoms more effectively.

Healthcare providers often recommend keeping a symptom journal to track the sequence, frequency, and severity of episodes. By identifying patterns, patients and physicians can work together to create a tailored treatment plan that anticipates the next cycle before it starts.

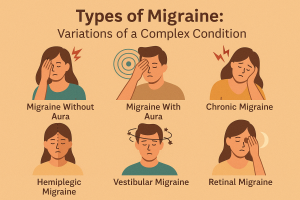

Types of Migraine: Variations of a Complex Condition

Classifying the Many Faces of Neurological Head Pain

While many people imagine a standard scenario of one-sided throbbing and nausea, this condition actually exists in multiple forms. The classification is essential for accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and personalized management strategies. Some variations are more common, while others are rare and often mistaken for different medical issues altogether. Each type has its own pattern, duration, associated symptoms, and potential triggers.

1. Migraine Without Aura (Common Type)

This is the most prevalent form, affecting the majority of individuals diagnosed with the disorder. It typically involves moderate to severe head pain that may last several hours to a few days. There are no preceding visual or sensory disturbances. Symptoms often include unilateral pain, sensitivity to light and noise, and gastrointestinal discomfort.

2. Migraine With Aura (Classic Type)

Characterized by visual, sensory, or speech-related changes that precede the pain phase, this type accounts for roughly 25–30% of cases. Patients may see flickering lights, colored shapes, or experience numbness and difficulty speaking. Although auras can be unsettling, they usually resolve within an hour. Recognizing this type early can help with proactive treatment before the pain phase begins.

3. Chronic Migraine

Defined as experiencing symptoms on 15 or more days per month for at least three consecutive months, this form is debilitating and often requires long-term medical intervention. The intensity of episodes may vary, and some days might involve only mild discomfort, while others bring severe, incapacitating symptoms. Chronic forms frequently overlap with medication overuse headaches, making diagnosis more complex.

4. Hemiplegic Migraine

This rare and dramatic form mimics the symptoms of a stroke. Individuals may experience temporary paralysis or weakness on one side of the body, speech difficulty, and confusion. Though frightening, these episodes typically resolve without lasting damage. Family history is a significant risk factor, and genetic testing is sometimes recommended for confirmation.

5. Vestibular Migraine

In this variation, dizziness and balance disturbances are more prominent than head pain. Patients often feel as though they are spinning, swaying, or unable to walk in a straight line. It can be triggered by motion, visual stimuli, or changes in position. This form is commonly underdiagnosed because its symptoms overlap with inner ear disorders and anxiety conditions.

6. Retinal Migraine

Also known as ocular migraine, this type involves brief, temporary vision loss or blindness in one eye. The visual episode may last a few minutes to an hour and is usually followed by typical headache symptoms. It is crucial to distinguish this type from other serious eye or vascular conditions that may require emergency care.

Understanding the specific form a person experiences is vital not only for effective treatment but also for lifestyle planning and emotional coping. Some individuals may shift between types over their lifetime, while others remain within a single category. Proper classification helps healthcare providers tailor strategies for prevention, medication, and long-term wellness.

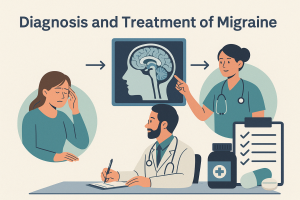

Diagnosis and Treatment of Migraine

From Symptom Recognition to Long-Term Management

Accurately identifying this neurological disorder is essential for implementing a treatment plan that improves quality of life. Unfortunately, many individuals suffer for years before receiving a proper diagnosis. Because its symptoms often overlap with other conditions—such as tension headaches, sinus problems, and even anxiety—misdiagnosis is common. A thoughtful and thorough evaluation is required to rule out secondary causes of recurring head pain.

Initial Consultation and Medical History

The diagnostic process usually begins with a comprehensive medical history and symptom review. Healthcare providers ask about the frequency, intensity, location, and duration of each episode. Details such as associated nausea, visual disturbances, and known triggers are essential. Family history is also considered, since this condition tends to run in families. Keeping a headache diary that tracks symptoms, foods, stressors, and sleep patterns can greatly assist this step.

Neurological Examination and Imaging

In most cases, physical and neurological exams are normal, but they help rule out other concerns. If red flags such as sudden onset, severe intensity, or neurological deficits are present, additional imaging may be recommended. CT scans or MRI are often used to exclude structural abnormalities, vascular issues, or tumors that could be mimicking symptoms. However, standard imaging tests typically appear normal in true migraine cases.

Treatment Approaches

There is no universal cure, but multiple treatment options are available to reduce the severity and frequency of attacks. These fall into two main categories: acute and preventive.

- Acute (Abortive) Therapy: Aimed at stopping an episode once it begins. This includes pain relievers (NSAIDs), triptans, anti-nausea medications, and in some cases, ergots. These should be taken as early as possible in the episode for maximum effectiveness.

- Preventive (Prophylactic) Therapy: Recommended for individuals who experience frequent or disabling episodes. This includes daily medications such as beta-blockers, anticonvulsants, certain antidepressants, and CGRP inhibitors. These treatments aim to reduce attack frequency and overall intensity over time.

Non-Pharmacological Strategies

In addition to medication, lifestyle changes play a critical role. Regular sleep, hydration, stress management, balanced nutrition, and avoiding known triggers form the foundation of long-term control. Techniques like cognitive behavioral therapy, acupuncture, biofeedback, and relaxation exercises have shown promising results for some patients.

It’s important to note that self-medication and overuse of painkillers can lead to rebound headaches, making the condition worse. Medical guidance is essential when planning both drug and non-drug interventions.

Ultimately, successful management requires a personalized plan. Collaboration between the patient and healthcare provider helps identify what works best. Some may respond to a simple adjustment in routine, while others may need a combination of therapies and regular neurological monitoring.

Prevention and Improving Quality of Life

Living With Migraine: Strategies for Daily Stability

While this condition cannot always be avoided, a well-structured lifestyle can dramatically reduce both the frequency and severity of episodes. Prevention begins with understanding personal triggers, prioritizing physical and mental balance, and developing habits that support neurological health. Many individuals learn to live full, productive lives by building their routines around consistency and self-awareness.

Identifying Personal Triggers

No two cases are exactly alike. What provokes one person’s symptoms may not affect another at all. Keeping a detailed journal of food intake, sleep patterns, stress levels, environmental exposures, and physical activity can help pinpoint common causes. Identifying and avoiding these triggers is often the first—and most powerful—step in prevention.

Establishing a Steady Routine

The brain thrives on rhythm. Irregular sleep, skipped meals, or dramatic shifts in daily habits can lead to instability in the nervous system. A regular schedule that includes consistent bedtimes, balanced meals, and gentle daily movement helps build internal resilience. Hydration, in particular, is often overlooked but plays a vital role in maintaining vascular balance.

Stress Management and Mental Health

Stress is both a trigger and a consequence of chronic head pain. Learning stress-reduction techniques is essential. Practices such as mindfulness, yoga, deep breathing, and guided relaxation can lower baseline tension and reduce the risk of neurological flare-ups. In some cases, counseling or cognitive behavioral therapy can address underlying anxiety that contributes to symptom intensity.

Medical Follow-Up and Long-Term Support

Consistent communication with a trusted healthcare provider makes a major difference in long-term outcomes. Adjusting treatment plans over time, exploring new medications or therapies, and evaluating lifestyle changes together ensures that the strategy remains effective and personalized.

At Concierge Medical Center, Dr. Tamta Bodokia provides individualized guidance and treatment plans for those managing chronic neurological pain. Her patient-centered approach is designed to support each individual through detailed assessment, education, and compassionate care.

Community and Education

Living with this condition can feel isolating. Joining a support group or online forum, reading updated research, and staying informed can empower individuals to take control of their health. Community engagement also helps reduce the stigma and normalizes open conversations about neurological health.

For more evidence-based strategies on managing head pain and neurological conditions, visit the Mayo Clinic’s Migraine Resource.

Prevention is not about perfection; it’s about progress. Each small step—whether it’s tracking your sleep, managing screen time, or scheduling follow-ups—can bring you closer to stability, comfort, and confidence.